Publish Date: 4 December 2025

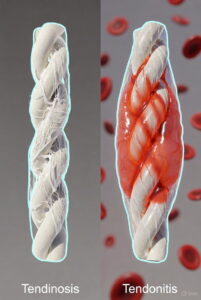

Tendonitis is acute inflammation of the tendon with swelling and pain that usually heals in weeks. Tendinosis is chronic degeneration of tendon collagen without significant inflammation and can last months to years. Understanding the difference is critical because the treatments are almost opposite. Most long-standing “tendonitis” cases are actually tendinosis. Correct diagnosis and loading-based rehabilitation lead to dramatically better outcomes.

Difference Between Tendinosis and Tendonitis

Almost every day a patient sits in my office and says, “Doctor, I’ve had tendonitis for six months (sometimes two years) and nothing helps.” After examination and imaging, I usually have to deliver the news: “You don’t have tendonitis — you have tendinosis.”

This single change in diagnosis completely alters the treatment plan and prognosis. For decades, medicine used the term “tendonitis” for every painful tendon, but research in the late 1990s and 2000s proved that the majority of chronic tendon problems show little or no inflammation. The difference between tendonitis and tendinosis is not just academic — it is the reason why so many patients fail standard anti-inflammatory treatments and stay in pain for years.

Understanding Tendinopathy: Tendons and Associated Conditions

Tendinopathy is the correct umbrella term that covers all painful tendon disorders. Tendons are dense, fibrous structures designed to transmit enormous forces from muscle to bone. Healthy tendons consist of 95 % type I collagen arranged in perfectly parallel bundles with very few living cells (tenocytes). Blood supply is naturally poor, which makes healing slow compared to muscle. Overuse, repetitive microtrauma, and faulty biomechanics are the common starting points. Age-related changes reduce collagen quality and elasticity. Certain medications (fluoroquinolones, corticosteroids) dramatically increase risk. Systemic diseases like diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and hypercholesterolemia affect tendon metabolism. Athletes in running, jumping, throwing, and racquet sports are most vulnerable. Office workers with poor posture frequently develop upper-limb tendinopathy. The Achilles, patellar, rotator cuff, gluteal, and elbow tendons are the classic locations. Early-stage problems are often reversible with load management. Advanced degenerative changes can become irreversible without intervention. Patient education is the most powerful tool we have. Misdiagnosis as “tendonitis” remains extremely common worldwide. Modern imaging and histology have completely changed our understanding. Treatment has shifted from fighting inflammation to stimulating regeneration. Loading, not rest, is now the cornerstone of successful rehabilitation. Research continues to refine protocols for different tendons and stages.

Anatomy and Function of Tendons

Tendons are brilliant biomechanical cables made almost entirely of type I collagen. Tenocytes sit between collagen fibres and maintain the matrix. The crimped pattern of collagen allows 2–4 % stretch before damage. Myotendinous and osteotendinous junctions are common rupture sites. Some tendons glide within synovial sheaths (flexor tendons), others are wrapped in paratenon (Achilles). Blood supply comes from vessels in the surrounding tissues. Avascular zones exist in many tendons (e.g., supraspinatus, Achilles watershed area). Ground substance (proteoglycans) maintains hydration and spacing. Fascicles are bundled together for strength and flexibility. Tendons adapt slowly to training but can increase stiffness and strength over months.

What is Tendinopathy? (The Umbrella Term)

Tendinopathy simply means “painful tendon disorder” and replaced the inaccurate term “tendinitis.” The continuum model describes reactive tendinopathy, tendon dysrepair, and degenerative tendinopathy. Reactive stage is potentially reversible with load reduction. Dysrepair shows matrix breakdown and increased cell activity. Degenerative stage has large areas of cell death and collagen disorganisation. Most chronic cases show mixed reactive-degenerative features. Ultrasound and UTC imaging can quantify structural change. Clinical load tests remain essential for diagnosis. Management depends on which stage dominates.

Tendonitis (Acute Tendon Inflammation)

True tendonitis is an acute inflammatory response inside the tendon or its sheath. It usually follows sudden overload, direct trauma, or rarely infection. Inflammatory cells invade within hours and peak in days. Classic signs of inflammation (redness, heat, swelling) may be visible. Pain is sharp, constant, and worsens with any movement. Symptoms typically resolve completely within two to six weeks. Complete short-term rest and anti-inflammatory measures work extremely well. Recurrence is uncommon if the inciting event is avoided. True tendonitis is actually quite rare in adults beyond the first few days.

Definition and Aetiology of Tendonitis (Causes)

Tendonitis literally means inflammation (-itis) of the tendon tissue itself. Acute mechanical overload is by far the most common cause. Direct contusion or crush injury can trigger it. Bacterial infection (septic tenosynovitis) is rare but serious. Crystal-induced inflammation (gout, pseudogout) occasionally affects tendon sheaths. Chemical irritation from certain drugs is possible. Paratenonitis affects tendons with paratenon (Achilles, patellar). Tenosynovitis affects sheathed tendons (flexor, extensor). Athletes after intense competition often develop it. Weekend warriors and sudden training spikes are classic patients.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Tendonitis

Pain begins suddenly, usually within hours of the inciting event. Local tenderness is severe and well-localised. Swelling is often visible and pitting. Warmth and redness may be dramatic in superficial tendons. Pain is constant and worsens with any attempt to use the tendon. Morning stiffness improves quickly with light movement. Crepitus or grating can be felt in sheath inflammation. Night pain is unusual unless severe. Symptoms peak within forty-eight to seventy-two hours. Rapid improvement occurs with proper treatment.

Histopathological Features of Tendonitis (Focus on Inflammation)

Neutrophils dominate the first forty-eight hours. Macrophages and lymphocytes follow within days. Increased vascularity and oedema separate collagen bundles. Inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, TNF-α, prostaglandins) are abundant. Collagen fibres remain largely intact and organised. Tenocytes show reactive hypertrophy. Plasma cells appear in prolonged cases. Healing occurs through normal inflammatory resolution. Fibroblasts lay down repair tissue within weeks.

Tendinosis (Chronic Tendon Degeneration)

Tendinosis is the correct term for chronic degenerative tendon pathology without significant inflammation. It represents failed healing after repeated microtrauma. Collagen becomes disorganised, weak, and filled with mucoid material. Abnormal blood vessels and sensory nerves grow into areas that were previously avascular. Pain becomes load-dependent and fluctuates with activity. Morning stiffness and start-up pain are hallmark features. Symptoms can persist for years without correct treatment. Progressive loading, not rest, stimulates collagen synthesis and remodelling. Anti-inflammatory treatments actually delay or prevent healing.

Definition and Aetiology of Tendinosis (Causes)

Tendinosis describes degenerative changes in tendon tissue (-osis = degeneration). Chronic repetitive microtrauma beyond healing capacity is the primary cause. Failed resolution of acute tendonitis leads directly to tendinosis. Aging reduces collagen turnover and tensile strength. Poor intrinsic blood supply prevents adequate repair. Repeated corticosteroid injections accelerate degeneration. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics are well-documented triggers. Metabolic diseases (diabetes, hyperlipidaemia) impair collagen quality. Genetic predisposition to poor tendon matrix exists.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Tendinosis

Pain develops insidiously over weeks to months. Morning stiffness lasts thirty to ninety minutes. Start-up pain improves after ten to twenty minutes of warm-up. Load-related pain increases throughout the day. Night pain occurs in advanced cases. Weakness and reduced performance are common complaints. Local nodular thickening is frequently palpable. Symptoms fluctuate dramatically with activity level. Complete rest brings only temporary relief. Chronic course with flares is typical.

Histopathological Features of Tendinosis (Focus on Degeneration)

Collagen fibres lose parallel orientation and become fragmented. Tenocyte numbers increase but cells appear abnormal and apoptotic. Mucoid ground substance accumulates between fibres. Neovascularisation brings chaotic new vessels. Sensory nerve ingrowth accompanies vessels and correlates with pain. Inflammatory cells are conspicuously absent or minimal. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) dominate over tissue inhibitors. Glycosaminoglycan content increases abnormally. Hypoxic zones and microcysts develop within tendon.

Core Differences Between Tendonitis and Tendinosis

Tendonitis is acute and self-limiting while tendinosis is chronic and progressive. Duration alone often separates the two conditions. Histology shows inflammatory infiltrate versus collagen degeneration. Treatment philosophy is completely opposite. Anti-inflammatory drugs help tendonitis but harm tendinosis. Complete rest cures most tendonitis but worsens tendinosis. Eccentric and heavy slow resistance training heal tendinosis. Imaging appearance differs dramatically between stages. Prognosis with correct management is excellent for both but requires different approaches.

Onset and Duration (Acute vs. Chronic)

Tendonitis has sudden onset after a clear inciting event. Tendinosis develops gradually with no obvious starting point. Tendonitis resolves in two to six weeks maximum. Tendinosis persists three months to years without intervention. Acute swelling dominates tendonitis presentation. Chronic thickening characterises tendinosis. Recovery from tendonitis is usually complete. Tendinosis requires active rehabilitation for resolution. Misdiagnosing tendinosis as chronic tendonitis is extremely common.

Underlying Pathology (Inflammation vs. Tissue Breakdown)

Tendonitis shows classic cardinal signs of inflammation. Tendinosis reveals disordered collagen and cell death. Neutrophils and macrophages flood tendonitis tissue. Tendinosis has few or no inflammatory cells. Neovascularisation is prominent in tendinosis. Vascularity returns to normal after tendonitis resolves. Cytokine profile is pro-inflammatory in tendonitis. Growth factors dominate in tendinosis. Healing pathways are fundamentally different.

Response Time to Treatment Modalities

Tendonitis responds within days to rest and NSAIDs. Tendinosis shows little or no response to anti-inflammatories. Eccentric loading improves tendinosis in eight to twelve weeks. Complete rest often increases pain in tendinosis. Platelet-rich plasma shows promise in degenerative tendons. Corticosteroids provide quick relief in tendonitis. Steroids weaken collagen long-term in tendinosis. Shockwave therapy benefits both but via different mechanisms.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis Methods

Clinical history is the most reliable way to distinguish the two conditions. Acute versus gradual onset is the first branch point. Physical examination reveals different tenderness and swelling patterns. Ultrasound shows peritendinous fluid in tendonitis. Doppler signal is markedly increased in tendinosis. MRI demonstrates inflammatory oedema versus degenerative signal. Blood tests rule out systemic inflammatory disease. Load testing reproduces symptoms differently in each condition. Palpation reveals soft swelling versus firm nodules. Patient age and activity level provide strong clues. Previous treatment response is often diagnostic. Biopsy remains gold standard but is almost never required. Ultrasound tissue characterisation (UTC) quantifies degeneration accurately. Functional assessment completes the clinical picture. Multidisciplinary approach improves diagnostic accuracy. Specialist referral is recommended for chronic cases. Early correct diagnosis prevents years of failed treatment.

Treatment Approaches and Rehabilitation Protocols

Treatment of true tendonitis is simple and anti-inflammatory. Short-term complete rest works perfectly for acute cases. Ice, compression, and NSAIDs provide rapid symptom relief. Gradual return to activity prevents recurrence. Tendinosis treatment focuses on mechanical loading to stimulate regeneration. Eccentric protocols (Alfredson, heavy slow resistance) are gold standard. Progressive tendon loading remodels collagen over twelve to twenty-four weeks. Platelet-rich plasma injections help recalcitrant cases. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy accelerates healing in chronic tendinosis. Topical glyceryl trinitrate improves outcomes in some tendons. Corticosteroid injections are absolutely contraindicated in tendinosis. Anti-inflammatory medication delays collagen synthesis. Physical therapy must be loading-based and progressive. Patient compliance and education are critical for success. Time frame for meaningful improvement is three to six months. Surgery is reserved for the tiny minority with complete rupture. Multidisciplinary management gives best long-term results.

Prevention and Risk Factor Management

Proper warm-up and gradual training progression prevent acute tendonitis. Strength and flexibility training improve tendon resilience. Technique correction eliminates faulty biomechanics. Appropriate footwear and surface choice reduce loading errors. Regular rest days allow tissue adaptation. Nutrition rich in collagen precursors supports tendon health. Weight management decreases cumulative stress. Stretching maintains optimal length-tension relationship. Cross-training prevents repetitive strain. Ergonomic workplace modification protects upper-limb tendons. Monitoring training volume and intensity catches early warning signs. Regular screening with ultrasound detects subclinical changes. Patient education remains the most effective prevention tool. Load management is the single most important principle. Early intervention stops progression from reactive to degenerative stage. Long-term tendon health requires ongoing attention and care.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ömer Bozduman completed his medical degree in 2008 and subsequently served in various emergency medical units before finishing his Orthopedics and Traumatology residency in 2016. After working at Afyonkarahisar State Hospital, Tokat Gaziosmanpaşa University, and Samsun University, he continued his career at Memorial Antalya Hospital. He now provides medical services at his private clinic in Samsun, specializing in spine surgery, arthroplasty, arthroscopy, and orthopedic trauma.